Words Ruairi O’Shea

Images Harry Talbot

In just its third year, Edition Zero has quickly become one of New Zealand’s most prestigious bike races. You might know who won but, with no television coverage, you probably don’t know how. This is the inside story of Edition Zero 2024.

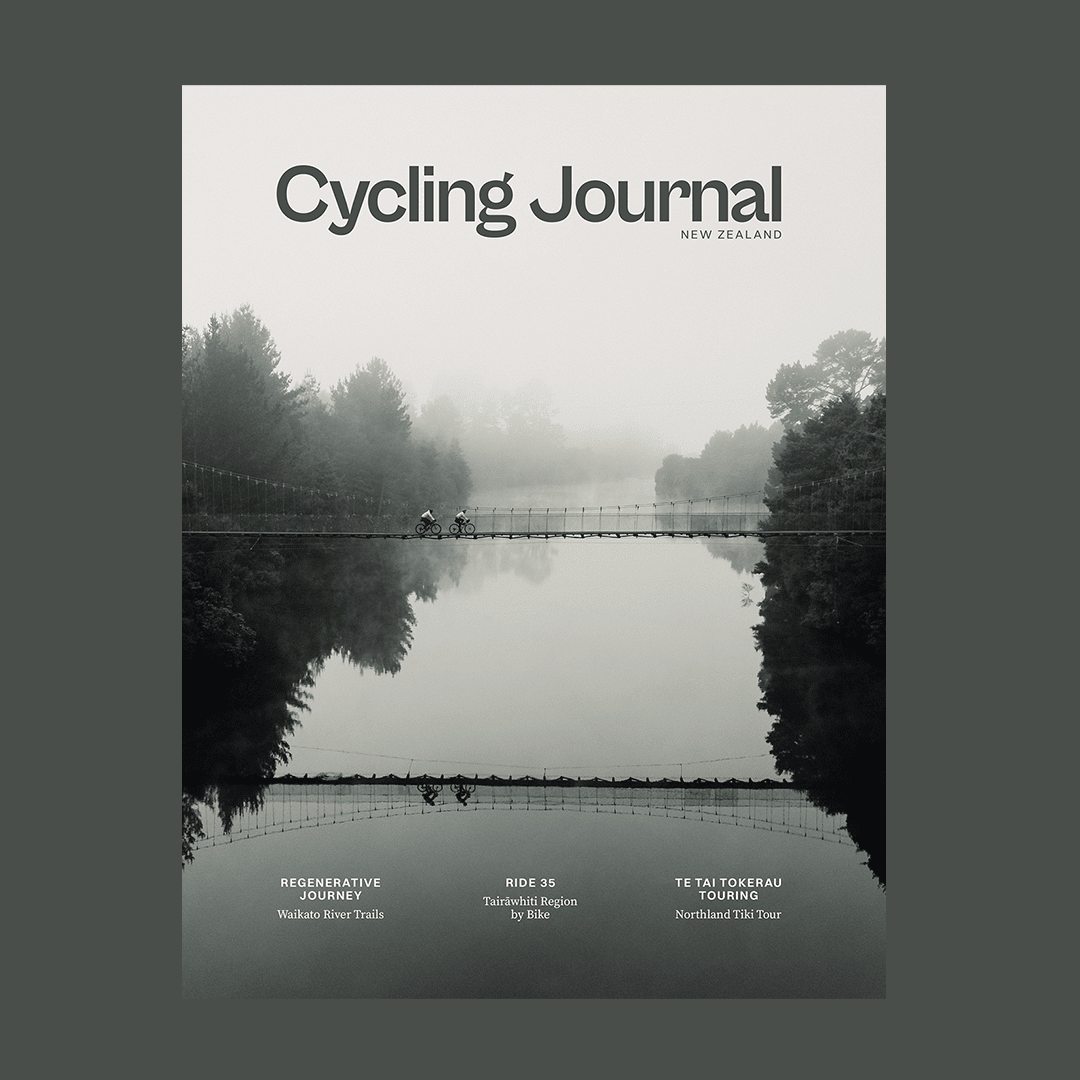

In the last weekend of November, cycling’s past and present collide in the small agricultural town of Waimate for Edition Zero, a gruelling 240 kilometre gravel race in the rolling farmland of South Canterbury.

With its spring date and velodrome finish, Edition Zero pays homage to Paris-Roubaix, but as a mass participation event with 3,400 metres of ascent, it has more in common with the new wave of American gravel races like Big Sugar, SBT GRVL or Unbound.

And while it might look like the best bits of cycling’s past and present have been copied and pasted onto New Zealand’s South Island, don’t be fooled. Waimate has a rich cycling heritage.

Far from a tribute to Roubaix’s velodrome, Waimate’s was built in 1891, five years before the first edition of Paris-Roubaix and more than 40 years before the completion of Roubaix’s concrete track.

Edition Zero is not the first long distance event to finish on the velodrome, either.

Between 1930 and 1950 the town hosted the start of the annual 233km race from Waimate to Christchurch, and from 1951 to 1954 the race was run in reverse. Almost 70 years before the first Edition Zero in 2022, West Coast coal miner, Cliff Carr, took the final Christchurch to Waimate leg following a 70 kilometre solo attack.

This history might be why the event’s founder, Andy Chalmers, speaks as if he discovered it lying dormant, waiting to be found, as much as having created it himself.

“A friend and I had a free weekend and a few options for a bikepacking trip depending on the weather. We settled on this loop out of Waimate and just went for a ride. It was purely a bikepacking overnighter, but I just started thinking about the race we could have.

“It’s 250 kilometres with no towns. There are smatterings of dairy farms, but it’s limited to the very start and end of the course. There isn’t a lot of traffic going up and down the roads every day, so the gravel is pristine,” Chalmers says.

“I was looking around on Google Maps and I saw the velodrome, and then I learned about the Waimate to Christchurch race…. we had this town with this rich cycling history. We’ve got a loop which takes on three distinct passes—Mackenzie Pass, Hakataramea Pass and Meyer’s Pass—and we’ve definitely got a finish line sorted.”

Edition Zero was born.

Andy is insistent that the primary reason for the event, its rurality, and its difficulty, is that the challenge helps to forge a community. But, when you put a load of people together on bikes and point to a finish line, you’ve got a race.

As the reputation of the event has grown, so has the quality of the field. “This year it was very evident that people had targeted it,” Chalmers says. “It wasn’t just another race on their calendar. It was something they were putting specific effort towards.”

But for those who had spent their winter preparing for a tilt at the victory, a spanner was about to be thrown into the works, with George Bennett—one of New Zealand’s most successful professional road cyclists—entering the race at the last minute.

For Bennett, Edition Zero offers a rare chance to race at home and in very different circumstances.

“Not one of the stresses overlapped, compared to riding in Europe,” Bennett says. “I was worried about aid stations; I was worried about getting there in time for sign on. I don’t know what you take on a gravel race. Do you take a pump, do you take tubes? What do you take?” he explains.

At a professional race, logistics are taken care of by an army of helpers so the rider can focus on racing. Mechanical issues are solved by raising your hand in the air and waiting for a team car, and information about what’s happening in the race is relayed by television cameras and team radios. At Edition Zero, he was on his own.

On the start line, Bennett describes a shared sense of foreboding. For many rolling out of Waimate that morning, it would be their longest day in the saddle. George might ride his bike for a living, but he was just as scared of the distance, and the event’s isolation, as the amateurs. “My biggest fear was getting a puncture early on and being stuck riding on my own,” Bennett says. “I was shitting it about riding 250 kilometres on gravel. No matter what, no matter how fit you are or where you’re riding, being on a bike that long is hard.”

As the bunch travelled north out of Waimate, hugging the Eastern slopes of Canterbury’s Hunters Hills, the pace was easy, according to Bennett, but as the race approached its first feed zone, a big difference between road and gravel racing was about to emerge.

It’s one of professional cycling’s unwritten rules that you don’t attack through the feed zone, but in gravel events the feed zone is more like the transition of a triathlon; valuable time, or your position in a strong group, can be lost through poor planning or execution.

“When we hit the first feed zone, I didn’t realise the pace that we’d go through those at and I dropped into the third group coming out of it,” Bennett says. “After that the race was on.”

Bennett was not the only rider who found himself out of position coming out of the first feed, with Palmerston North’s Caleb Bottcher fumbling what should have been a simple drop-off after 70 kilometres.

Bottcher is a 24 year-old mountain bike racer who works full time as an accountant. Edition Zero was his first gravel race and while he’d planned his feeds meticulously, failing to disentangle himself from his Camelbak almost ended his race before it could begin.

“My plan there was just to be dropping my Camelbak,” Bottcher says. “I’d still have two bottles and full pockets. When I got there my mind blanked. I still had the bag clipped up and the hose strapped across me.”

As the lead group split into three, Bottcher was badly out of position. He took comfort that he was in a group with Bennett, but when George rode across to the lead group, Bottcher missed the move.

“I started to really panic,” Bottcher says. “This group was not working well together, and we were watching the gap just get bigger and bigger to the two groups in front. I thought I’d blown it.”

For Bottcher, who came to Edition Zero for a place on the podium, this was a pivotal moment in the race.

There’s a train of thought in endurance sport which says that the brain limits our exertion before our body does. It’s in our nature to want to feel safe, and to preserve our resources, and events like Edition Zero pit an athlete’s desire to achieve a goal against their instinct for self-preservation.

“In an eight hour race, there’s going to be dark patches, and there’s lots of time to think, so how you shape that has a huge impact. Bad things are going to happen in that time, so it’s how you manage those moments and your reactions to them which is what matters,” Bottcher says.

Soon, an opportunity to make up some ground presented itself as the road banked sharply uphill. Caleb gave it everything, reaching the front group and turning the tide in the battle with his negative thoughts.

“Having to go so deep so early was not good, but I talked myself out of it. The other guys have maybe had a bit of a nicer, smoother effort, but everyone’s had to do something that’s not ideal.”

Before long, Caleb was proven right. “I started to hear some murmurs from a few of the other guys in the group, saying things like ‘oh shit, we’re not even halfway’.”

Caleb describes himself as a naturally calculated rider, and when he talks about the race it’s clear he is constantly weighing up a range of variables— the state of the race, how strong he’s feeling, and how strong the competition appears to be—to give himself the best chance of winning.

In the past, this has led to conservatism in his racing, and he’s worked hard to develop a more impulsive side to his riding. When he hears signs of weakness from the other riders in the front group, he decides to take the race on.

“George pulled a turn, I pulled a turn, and then no-one pulled through after me. I didn’t want to look back, but I glanced under my shoulder and there was no-one there…I just thought, ‘you guys are going to regret that’, and started turning the screw,” Bottcher says.

With 130 kilometres, and the race’s three main climbs—Mackenzie Pass, Hakataramea Pass and Meyer’s pass—still to ride, Caleb was on his own. This was not a rush of blood to the head, with Caleb’s attack representing a perfect blend of the calculated style that comes naturally, and the impulsive side he’s worked hard to develop.

“I’d run a couple of scenarios in my head before the race…I wasn’t sure how it was going to play out, but I was open to going early. It wasn’t Plan A, but if an opportunity arose, I wasn’t going to turn it down. Morale was a bit low; no-one pulled a turn after me… I just decided to take it on.”

The first major obstacle was the Mackenzie pass, a four kilometre climb with an average gradient of 6.3%.

“The Mackenzie Pass was going to be telling as to whether it was going to be a day in a group of two or three, or a day by myself. If they get back to me on there, they’ll have had to put in a huge effort to do it. That will be plus one for me. Whichever way it turns out, I’m going to need to ride really hard and be tactically smart, but this is going to decide in which way.

“When I rolled over the top by myself and saw that they were maybe a minute behind me, that’s when I knew it was just going to be me, and that I needed to start building the gap that they’d be eating into later.”

Caleb began his descent into the Mackenzie Basin. “This is big sky country,” race organiser, Andy Chalmers, says. “You’re looking straight at the Southern Alps; look to your right, and you can see Mount Cook. Then you’re climbing through the Hakataramea valley.”

Over the course of the 13 kilometre Hakataramea Valley, Bottcher put another three and a half minutes into his competition, adding another minute to the gap on the descent.

By this stage, Caleb had been riding alone and without a time check—letting him know the gap to the chasers behind—for over an hour. “If I’d got smaller time splits earlier, you might be questioning whether it’s working or not,” Bottcher says. “Not knowing let me just give it everything.”

While Caleb had been blissfully ignorant at the front of the race, the chasers were in for a shock.

Having seen Bottcher take a wrong turn early in the race, there was an understanding in the group that he didn’t have the course loaded onto his GPS, according to Wanaka’s Jeremy Presbury.

“After a while of him being off the front and not being anywhere in sight, I assumed he’d taken a wrong turn at some point and that was his day done,” Presbury says. But when the group was told that Caleb was still on the course, and that he had put seven minutes into them, there was disbelief.

“There were a few ‘what the fucks’ going around,” Presbury says. “I had no idea who Caleb was, so I remember thinking ‘who the fuck is this guy?’. At that point, we all just knew that we needed to work together to bring him back.”

As the chasers swapped turns to bring Caleb back, the gap began to come down, but after a long day on the pedals, the group began to deteriorate. When the road ramped up for the 11 kilometre climb up Meyer’s Pass, the chase group was down to three: Finn Mitchell, Sam Shaw and George Bennett.

Over the course of Meyer’s Pass, the group clawed back two minutes on Bottcher. Shaw punctured 100 metres from the top, before Mitchell and Bennett took back another 30 seconds on the descent. With around 25 kilometres to go, Bennett eased away from Mitchell and it was Bennett vs. Bottcher for the victory. Caleb’s long day out, and Bennett’s World Tour legs, were about to show.

“I knew the gap was coming down and I turned onto the highway and into a pretty strong headwind and I knew that was going to be the undoing of it… I got told I still had a minute left, and I was dying on a slight rise; standing up, sitting down, standing up, sitting down. Sure enough on the run down from this hill I just felt a little tap on the hip from George, and I was done.”

Bottcher was caught, but his gamble had paid off and as he took the second step on the podium he could be proud of a huge personal achievement. “It’s really important to have proven to myself that I can ride like that. It’s a personal victory,” he says.

For Bennett, who lapped the velodrome four minutes ahead of Bottcher and the rest of the field, it was not only a rare home victory, it was one of his hardest days out on the bike. “It’s a very specific event to just be strong for eight hours and the accumulated fatigue is massive. It’s one of the biggest races I’ve ever done for energy expenditure… it’s a death march.”

Waimate velodrome may not have the glitz and glamour of road racing at the highest level, but for Bennett, this is what he was after.

“You don’t go to Edition Zero looking to replicate a road race. I got to see this unreal part of New Zealand and I got to experience this bike race that was diametrically opposed to what I do for my day job. Seeing the volunteers at the velodrome, everyone lining up at 5:30 in the morning with their blankets on, and then seeing the community come out to see the finish, eight hours or 12 hours later in some cases. It was everything I’d hoped it would be.”

For Andy Chalmers, this is music to his ears.

“The race is an adventure. You’ve got to navigate yourself; you’ve got to look after yourself, and you’ve got to sort your own nutrition. We put on aid stations, but you’ve got to make those decisions to get yourself through it. It’s a challenge. It’s going to be really hard. But the point of that is to bring people together around what they’ve achieved.”

Edition Zero takes place on November 29th 2025. Get out there.