Words: Liam Friary

Images: Marcus Enno

Dialogue Introduction

We’re in Auckland, hustling to get our bikes and gear packed into a cardboard box before biffing them into the boot and driving to the airport. As we’re due to catch a plane, there’s a hard deadline and we’re slightly anxious. Phew, the bikes are now packed!

Sweet, now we’re in transit to the Auckland Airport. Traffic isn’t playing ball – as per usual here in the city – and a half hour trip quickly turns into an hour. We scramble to the drop off zone, throw the bike boxes onto a trolley and move quickly towards Departures. We arrive at the Air Chathams check-in desk to find just one person in the line ahead of us, maybe things are going our way after all? Our airport check-in is done and dusted in under three minutes. We board the small plane, nicknamed Swedish Princess, and fly from Auckland to Whanganui. It’s a beautiful evening and the sun is setting on the west coast as we touch down on the runway. We unpack our bikes and then build ‘em, ready for the adventure ahead; the Whanganui Airport workers ask us to move outside as they’re closing the airport – it’s only 7:30pm but we are in the provinces now and I like it! Bikes built, we bundle them onto a trailer and jump into the van that’s towing them. We transfer to Ohakune and after a few hours we’ve arrived at the Powderhorn Chateau. It’s a little late, just gone 10pm, but they’ve made dinner and kept the bar open for us – great service! – so we can have a feed and beer as soon as we arrive. Before long, we crawl under the covers and as we sleep, we dream about what might come of our adventure, which would see us – me, Phillipa and Marcus – riding the Mountains to Sea – trail over three days.

Dialogue Entry – 1.0

I’m excited about the day ahead so I jump outta’ bed, wipe some sleep from my eyes and stroll into the breakfast room. Ben Wiggins from TCB Ski Board Bike meets us downstairs, excited to be guiding us through his fine region. Ben is a free skier and is a real ‘Kune (Ohakune) advocate. Turns out, he’s one of the men behind the town turning into a ‘bike friendly’ place and has been involved in numerous projects with trail development. The next phase is a new mountain bike trail that will take you from the top of Turoa ski fields, all that way down to Ohakune. This has been a seven-year project and there’s a few more hoops to jump through before the building can start, but as you can imagine Ben’s stokin’ about this and has been heavily involved in the project. After breakfast and several coffees, we embark on our first day. Served up first was Turoa’s Mountain Road – there’s nothing like the country’s only Hors category climb to get you out of first gear. The ascent is stunning and has amazing surrounds with myriad changes in vegetation – from dense bush to open scree slopes and everything in between. After a tough ascent and superb descent, we ride back down into town (Ohakune) for some kai. Ben, who’s a real host and great talker shares several stories and we grab a few ride snacks as we won’t see anything after this, until we hit the outskirts of Whanganui. Our next journey would be Old Coach Road which would connect us with Horopito. This trail takes in some epic sights and offers more of a challenge if you ride it this way. It’s not too technical and can be ridden on drop bars, but you’ll need to slow down in certain spots – the sights are awesome anyway, so why not go a little slower?! Ben had stashed some beers for the Hapuawhenua Viaduct – this guy is the man! Back on the trail, tall ferns line the trail and the remains of old railway lines can be found.

The Old Coach Road once formed an integral link between the two rail heads, between 1906 and 1908, allowing through journeys by horse and coach before the railway was completed. The Hapuawhenua Viaduct was one of the final components of the North Island main trunk railway, and was built in 1907 and 1908. Hardy workers lived onsite during the two years it took to construct the viaduct, enduring harsh winters, primitive conditions and isolation to complete construction in time for the opening of the railway. There’s a ton of heritage features on the trail, including a unique cobbled road, massive steel viaducts, a curved tunnel, railway bridge remains, and old campsites.

Horopito is the end of this section, but the beginning of Smash Palace. As work gangs laying the North Island Main Trunk rail line from Auckland and Wellington, moved inexorably closer together, temporary work camps moved with them. Horopito was one such camp, but by 1908, with the completion of the line, it became obvious that Horopito was to be more than a work camp – a saw milling industry had started to establish itself in the district. However, in spite of this, Horopito never really thrived. It depended on sawmilling and railway traffic for its existence and by the late 1950s,with the native forest cleared, the decline had set in and most of the small population had moved on. The school closed in 1966 and the Post Office in 1971.

Sometime during the mid-1940s, Bill Cole arrived in town and established a motor garage and repair shop in what was originally a sawmill with a cookhouse/ bunkroom. He milled existing trees off the property with his own sawmill! Bill’s philosophy was that if a car came into the yard for dismantling, whatever parts were not sold would stay there. Nothing was scrapped – which explains the vast collection of parts that are here today. To the best of our knowledge, this yard is unique in Australasia and a like establishment would be a rather rare occurrence elsewhere. In 1981 the noted New Zealand film, Smash Palace, was filmed here and consequently Horopito Motors is known internationally. Bill passed away in 1987, but Barbara Fredricksen and her husband Colin now operate the business. This place is unreal and takes you on a journey through time, as there’s wrecked cars from every era. It’s a really cool place to look through and is worth a visit.

After the tour around Smash Palace, we wave goodbye to Ben and continue on with our journey. At this point, we cross the highway and take Middle Road onto Ruatiti Valley Rd. We’re tired by this time, and only just realise it’s another 29kms from there! We scoff some fuel and hustle down the valley; switchbacks, rolling hills and narrow roads with the Manganuioteao River running beside us, the sun glistening on it. We arrive at Ruatiti Domain, sit on the bridge and sip some water. It’s now 7pm and the sun is shining at its golden hour. We turn around to see sheep running down a hill, dust blowing out as they scramble down the banks – an amazing sight. The farmer rolls down the hill in his ATV for a yarn – turns out he has 800 sheep running down his paddock and needs to get them into another area with better water supply, after the super dry summer that we’ve been experiencing. We talk about each other’s jobs – he liked the sound of mine and I liked the sound of his – then we both continue on with the rest of our day.

Marcus is now on a mission, and Philippa is hitting it as we hit the final hour. We’re all buckling – it’s getting over the six-hour ride mark by this point. We make it to the Ruatiti Station Lodge, sit on the lawn and drink a beer – it’s never tasted better!

Dialogue Entry – 2.0

The best thing about taking a journey along an NZ Cycle Trail is that you get to meet great hosts and guests at the accommodation dotted in and around the trails. On this occasion we manage to have breakfast with the other crew that are staying with us – turns out they’re a real hoot! The owner of the station, Brent Greig, takes us on an adventure over his farm, where we learn about the land and watch the manuka honey process. Marcus even gets into a bee suit and gets amongst the hives!

Brent runs Wilderness Valley Honey and is kind enough to give us a few jars, which we stuff into our bikepacking bags. I like the way you discover information about an area when taking these trips. A bike takes you into remote places at a slow enough pace for you to get a real sense of the people and landscape, and I always welcome the opportunity to learn more about the lay of the land.

Both the Mangapurua and Kaiwhakauka Streams are tributaries of the Whanganui River. These valleys were rehabilitation settlements where land was offered to soldiers following World War I. The endeavours of these pioneers provides a unique historic quality to this area. The pioneer settlers cleared the land of much of its virgin native forest and transformed it into farmland. At the peak of settlement, there were 30 farms in the Mangapurua and 16 in the Kaiwhakauka. Today, only chimneys, exotic trees and hedges mark the remains of the house sites. Problems such as poor access, erosion and falling wool prices during the Depression years, forced most of the settlers to abandon their farms. The few remaining farmers were forced to leave the valley in 1942 when the Government refused to maintain the storm damaged road.

After the farm tour, we roll out and venture into the Mangapurua Track, which has been closed since last April. Thankfully, after a ton of mahi from DOC, it’s now open again. The initial climb to get you up to the trig isn’t too taxing as it’s a good gradient, and gives you amazing views as you get higher. Looking back, you can see Mt Ruapehu, Mt Tongariro and Mt Ngauruhoe. After this, it’s a descent and then mostly flats, and we’re stokin’ that the hard stuff is done. The descent is rowdy, dusty but oh-so damn fun. It flows well, of course there’s some choppy sections – it’s papa-rock after all – and we’re on drop bar rigid bikes. As its been bloody hot, it’s real dry and dusty. We hoot and holler as we ride down the track that was cleverly chopped into the native bush, under thick dust clouds. As the track takes us closer into Mangapurua Landing it turns to single-track as its passes across several bluffs. It’s here we realise the scale and severe steepness of the Whanganui National Park.

As we move down the valley, we cross the grassy clearings that were created by the early settlers. Many of the papa bluffs are named after settlers that farmed the surrounding land. The names of these settlers also live on in the wooden signs installed along the track, marking the location of the original house sites. After this, the valley becomes very narrow for a distance with the track meandering around a series of bluffs. The track hugs Mangapurua Stream before descending towards the Bridge to Nowhere. A key site here is Battleship Bluff, named for a feature across the Mangapurua Stream, resembling the prow of an old battleship. This bluff posed the greatest difficulty for the early road builders. Two years were spent terracing the bluff from the top, using gelignite. Outta’ nowhere, we turn onto the historic Bridge to Nowhere. This is a large concrete bridge that was completed in 1936, now standing abandoned in the bush, literally in the middle of nowhere. By the time the bridge was constructed, the lower valley had been abandoned by the settlers. From the concrete bridge, you can see the remains of the old suspension bridge used between 1920 and 1936. This old bridge, and its two predecessor wire cages, were vital to the initial settlers for the transport of all supplies.

We arrive at the Mangapurua Landing and await our jet boat transfer. Bridge to Nowhere Tours rolls up to the landing with their bright yellow boat, and the driver – Joe Adams – jumps onto the landing and nearly shakes my hand off! He’s been on the river for years and takes us up to his lodge along the way, which is nestled deep in the Whanganui National Park wilderness. We jump onto some quad bikes to get from the boat up to the lodge, and stroll in to find the same crew from the Ruatiti Station Lodge the previous night, sippin’ beers after a day on the pedals! We pull up a pew and join ‘em. The deck of the lodge overlooks the stunning Whanganui River, an amazing location that can only be accessed by boat; we look out and reflect on the journey.

A little late on, we jump back into Jo’s jet boat and take another ride down the Whanganui River in the shimmering sun; the evening light has the Whanganui National Park bush in darkness and the river bathed in light, the sun glistening off the water. We arrive at Pipirki, a low-key landing where the road and Mountains to Sea trail begins again. From here, we pedal a few clicks to Jerusalem, where we’d arrive at our digs for the evening – the Old Convent.

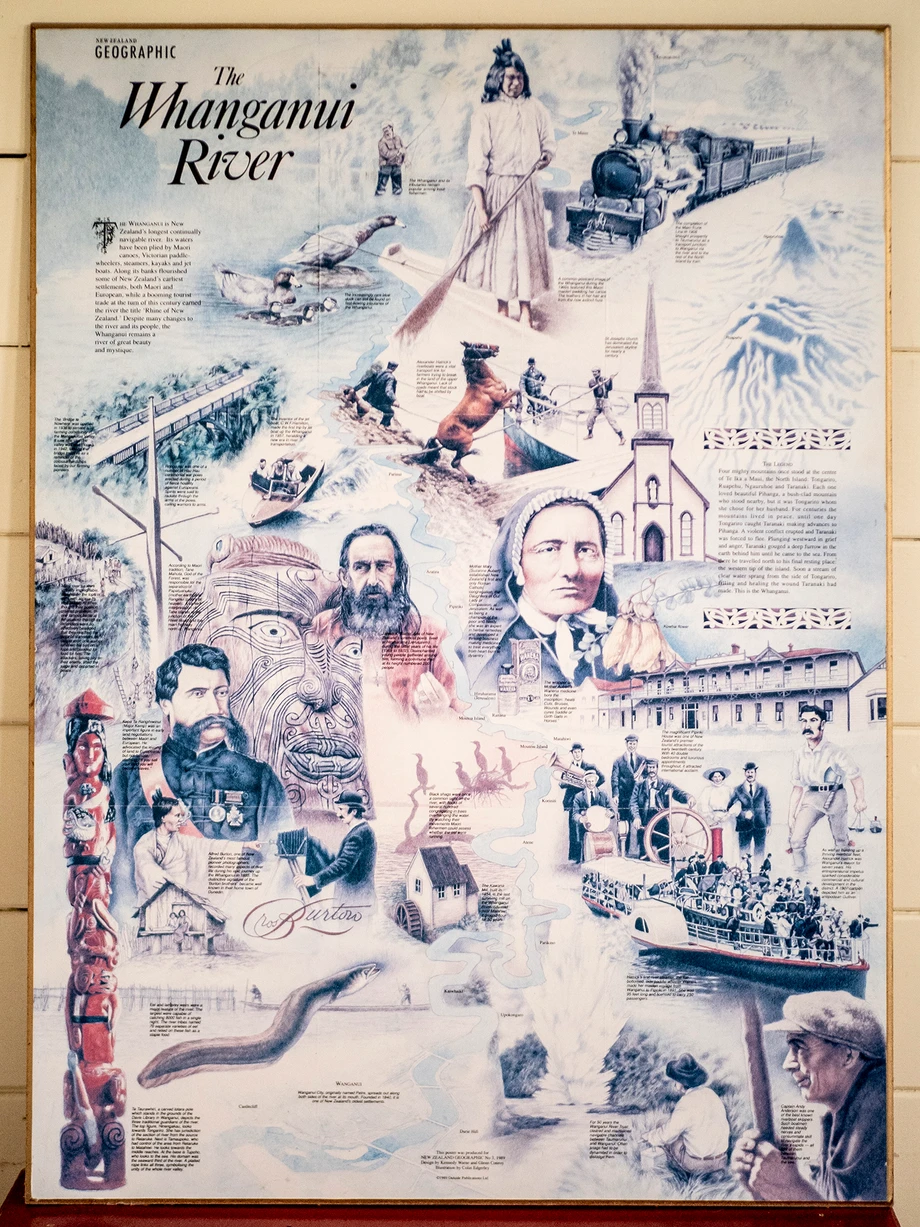

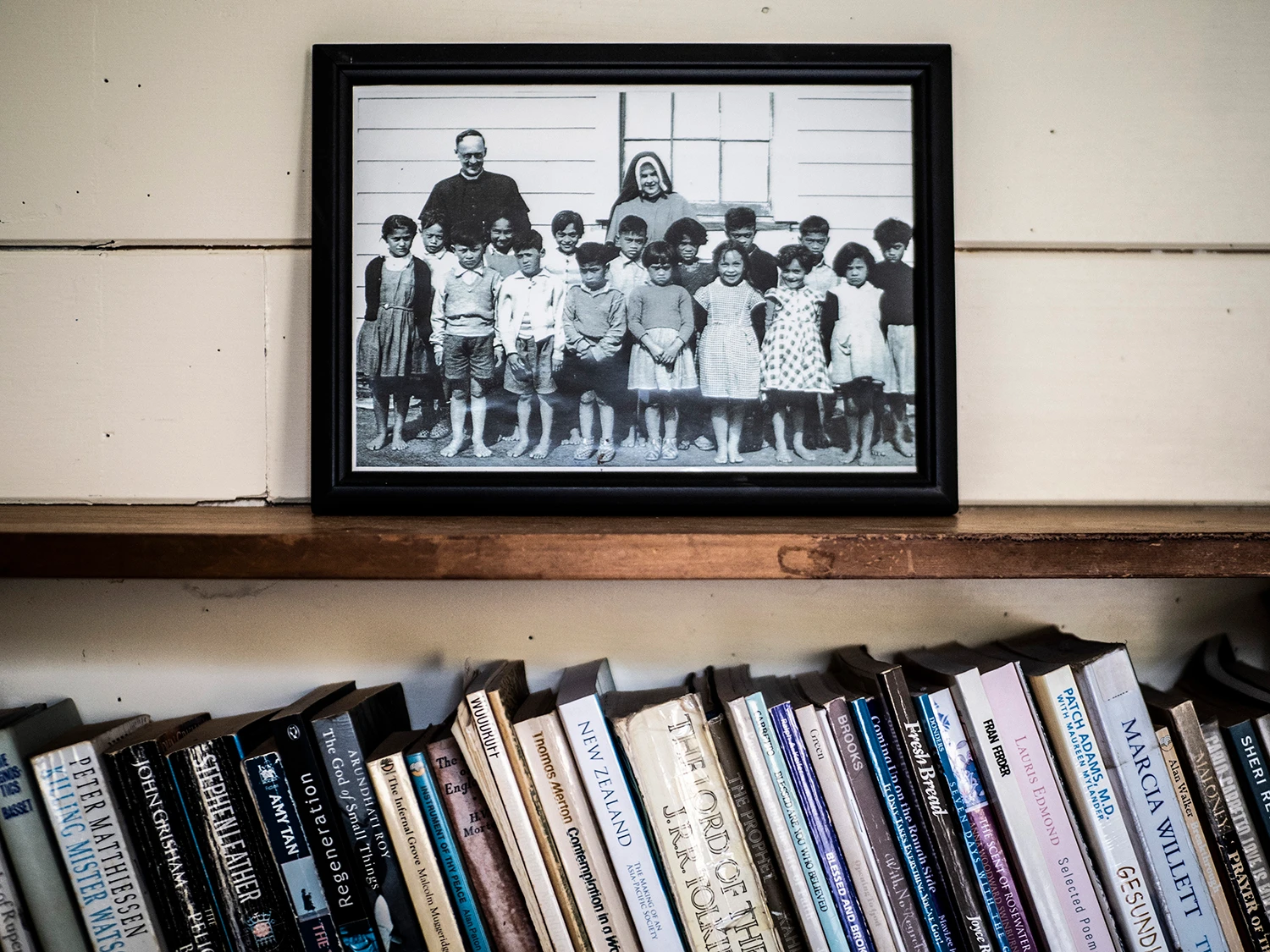

Jerusalem, or Hiruhārama in Māori, is a tiny settlement on the Whanganui River Road and a special place within Aotearoa’s history. It was originally called Patiarero and was one of the biggest settlements on the Whanganui River in the 1840s, with several hundred Ngāti Hau inhabitants of the iwi Te Āti Haunui a Pāpārangi. Many Whanganui River settlements were given new place names by Reverend Richard Taylor in the 1850s. Jerusalem Whanganui was an isolated site where, in 1892, Suzanne Aubert (known as Mother Mary Joseph) established the congregation of the Sisters of Compassion. They became a highly respected charitable nursing and religious order. Also established, was the Jerusalem Foundling Home in 1886 which housed and cared for abandoned children from around New Zealand. A convent remains in Jerusalem, as well as the church where the Sisters of Compassion still care for the buildings and the history of the site.

Whilst there, we learn about Suzanne Aubert through her pictures, quotes, books and even a VCR tape which we watch. Suzanne Aubert was a determined young woman who, as soon as she was legally free to decide her own future, left Lyon in France to begin her lifelong spiritual journey. As a young woman, Suzanne repeatedly but unsuccessfully asked her parent’s permission to join the religious life. Finally, at age 25, with the freedom to decide, she accepted an invitation to become a missionary for Bishop Pompallier’s Auckland diocese. After working initially at a boarding school for Māori girls, Suzanne left Auckland to work at the Marist Māori mission station at Meanee in Hawke’s Bay, with the Third Order of Mary. She became well-known in the area ministering to Māori and Pākehā, Catholic and non-Catholic, without compromising her own beliefs. Tolerance and friendship became strategies for her mission. In 1874, Suzanne was pinning her hopes for a revival of the Māori mission on the new Bishop of Wellington, Bishop Redwood, who was to become her lifelong supporter. In 1883, by invitation of Māori from the Whanganui River area, Suzanne left Hawke’s Bay for Hiruhārama – Jerusalem – to revive the Catholic mission.

In the 1880s, the only way to travel up the Whanganui River was by canoe, and this is how Suzanne reached Jerusalem in June 1883. With her were three Sisters of St Joseph of Nazareth, two of whom would be her companions, along with Father Christophe Soulas SM, in reviving the Māori mission. Jerusalem is where Suzanne spent the next 16 years of her life making many trips to Whanganui.

Dialogue Entry – 3.0

Birds chirp in the early morning, on the grounds of The Sisters of Compassion Catholic Convent. A tranquil place to see a new day in, unfortunately we can’t stay any longer as we need to hustle to make a 3pm flight from Whanganui, which is a few hours away. This is the final part of the trail and, whilst it’s all on the sealed road, I’d have to say it’s one of the best parts of the adventure. Here, you can find out a lot more about Maori history and culture, as the route rolls and hugs the riverbanks.

“E rere kau mai te Āwanui, Mai i te Kāhui maunga ki Tangaroa Kō au te Āwa, kō te Āwa kō au.”

“The great river flows from the mountains to the sea. I am the river, the river is me.” This whakataukī (proverb) defines the Iwi (Māori) of the Whanganui River and region. From the sacred mountains of the Central Plateau, the Whanganui River begins its journey of nearly 300km and is eventually released into the Tasman Sea, off the western coastline of Whanganui. Along its length, the people of Te Āti Haunui-a-Papārangi (Whanganui Iwi) have descended over 40 generations.

Negotiation for purchase of land with Whanganui Māori started as early as 1840, and was finalised in 1848 when 80,000 acres were purchased.In 1841, the first settlers from England, Scotland and Ireland arrived in Whanganui and by the early 1900s business in Whanganui was booming. The Whanganui River tourist trade took off, with thousands of passengers being transported on Alexander Hatrick’s riverboat fleet. Hatrick made the river accessible to everybody: rich tourists, farmers in the interior, and Whanganui citizens. Whanganui thrived as it serviced a huge fertile agricultural catchment area, rearing sheep and cattle, as well as growing barley, wheat, oats, maize, fruit and timber. Seven kilometres upstream from the river mouth, the town was developed and wharves established. Most coastal shipping berthed just downstream from the present town bridge. The Whanganui town wharf was the centre of activity until 1908, when Castlecliff Port was developed around the frozen meat trade. The town wharf closed in 1956, as it was uneconomic to operate both ports.

Rolling along the river road is pretty beautiful, and the speed is welcomed after the mixed terrain riding over the past few days. We’re surround by high mountains as we wind our way alongside the Whanganui River. There’s so much to see along the route, and riders can stop at certain points to learn about the region and its historic sites, such as Kawana Mill. This mill was originally named Kawana Kerei (Governor Grey) in honour of the governor, who donated millstones. Millwright Peter McWilliam built it in 1854 at Matahiwi, for Ngā Poutama iwi to take advantage of salvageable totara logs lying in the riverbed. The provident Whanganui also provided transport for Grey’s millstones and English cast-iron machinery and brass bearings, as well as powering the waterwheel that started turning inside the timber-framed, three- storey weatherboard mill house.

Gentle Annie’s grip doesn’t show mercy, but after that it’s downhill and then a transfer to Whanganui. The road takes us into Upokongaro which is a little village with a ton of character and charm, nestled on the Whanganui riverbanks. We carry on, battling head and cross winds – Philippa and I try to hide from the wind behind Marcus, who’s a rather tall lad. Eventually, we’re on Whanganui’s cycle path, which gets us to North Mole – a moody, driftwood-strewn beach where the Mountains to Sea journey ends. We spot the markets, beside the river, and head over for a quick browse. We end up in an alternative art cafe by the name of Article Cafe. Its coffee, art and unusual ornaments make the transition from off the grid to on the grid somewhat hard. I have some time, however, to find an old school rugby jersey in the op shop inside as we queue for coffee. I have to say, Whanganui’s got real charm; it’s arty, quirky and has a cool vibe. After we caffeinate, we hustle to the airport and pack down there, as our contact had left our bike boxes at the Pilot Academy.

Having checked ‘em onto Air Chathams, we eat mince on toast and board the hour-long flight back up to Auckland. We fly back over Mt Ruapehu, reminiscing our incredible journey.

Dialogue Summary

The best thing was only being away for just three and a half days – it was a lot to pack in, but it’s achievable. As I’ve said before: trips like these feel like an eternity, as you’re away from other distractions in life. A short amount of time doing this feels like a long time once you return home. Don’t get me wrong; the planning, packing, itineraries, transfer hustle and everything else is a lot of work, but the reward and outcome is always worth it. Plus, you have incredible memories etched into your mind. It’s like anything in life; you get out what you put in. Mountains to Sea – Ngā Ara Tūhono covers some diverse landscapes, totally unique to this part of the county; linking roads across mountains, trails in the dense jungle-like bush, then taking you into historic sights, trials across harsh land and boats which take you down river. Plus, you get a taste of Maori heritage along the river, making this trial well worth doing. It’s a real adventure ride and showcases how amazing Aotearoa, and especially this part of the North Island, really is.