Words: Liam Friary

Images: Chris Auld & Gruber Images

Socks are filled. Suntan cream is applied. Numbers are pinned. Jokes are had with the team and staff. The vibe is good. Rental vans and cars replace team cars and buses. And I’m introduced to Italian Stefano Deicas, who has worked as a soigneur for almost thirty years. He’s a typical Italian: slight, olive skin, cheeky smile and a thick Italian accent. He greets me with “Buongiorno” as his strong handshakes mine.

I’d managed to wrangle a ride in the EF Education First-Drapac p/b Cannondale swanny car for stage two of the Giro d’Italia. I had tried to line up a ride in the team car (the one that follows the peloton) but as soon as Jonathan Vaughters (owner of the team) arrived I got bumped down the list! This was, however, quite an exciting opportunity, as we don’t get much access to this high level of racing. And it really showed me how much hard work goes in behind the scenes.

In the team car park, I spotted Tom Scully getting ready to start the stage. He will be part of the sprint lead-out train for Sacha Modolo. Tom packs his rice cakes and a few gels before quickly jumping back in the van for shelter from the oppressive heat in Haifa, Israel.

On EF-Drapac p/b Cannondale there are twelve soigneur staff, five for the Giro d’Italia. They cover different races depending on the schedule; on grand tours they rotate jobs once a week to keep things fresh. At the Giro d’Italia start in Israel, the swanny cars don’t have race radio—the only radio is the one playing Hebrew music in the rental Avis.

We head off on the race course to the first feed zone. The two Italians, Stefano and Luca Fattori (who has been a soigneur for 20 years), chat away, talking about the Kiwi riders they have worked alongside, such as Tom Scully now and Jack Bauer two years back. They talk highly of them—mainly Jack. Over the years they had developed a strong relationship with him, and he still greets them at the various races now. Stefano says, “He’s a good guy, always makes jokes, and is always calm.” Luca says, “He’s always nice with the fans and great around the dinner table, always wants [to] chat.”

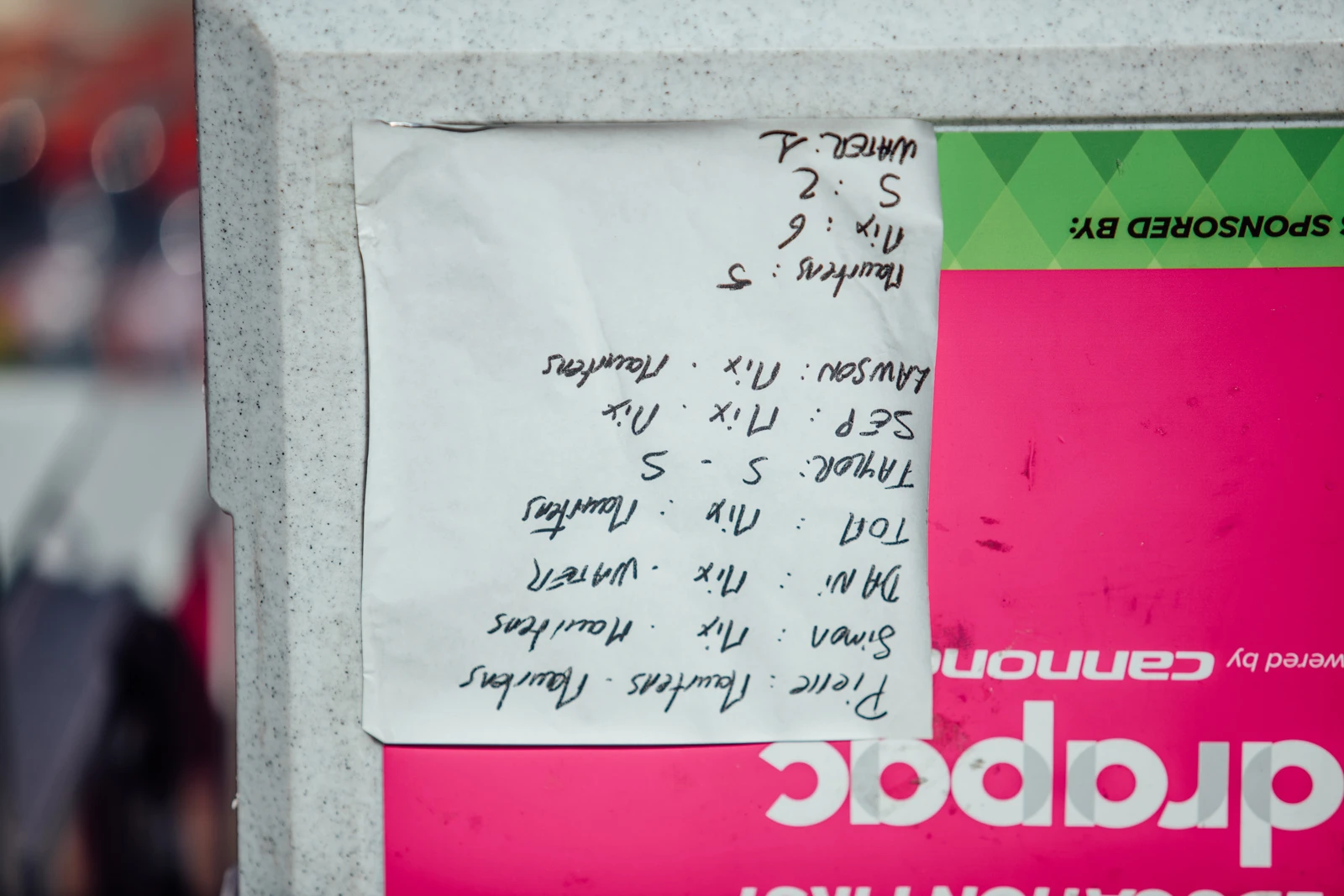

After around 80 kilometres of driving we arrive at the feed zone. The swanny cars roll up and there’s a bit of banter between everyone. I noticed that the teams swap food, drinks and whatever else is needed for their riders. In such a tight-knit sport it pays to help each other out; what goes around, comes around. The peloton approach the feed zone going full gas, as the run is quite flat with only a small incline. The riders are trying to pull the break back so they hit the zone with pace: out of the eight riders, only two or three take the musettes. The bag-and-bidon pass to riders requires a certain feel that you have to learn over time. These two are experienced hands. The swannies give the remaining musettes to the first follow vehicle. Luca says, “Some riders will always grab a bag, and some don’t. But they get down in the race and it makes it difficult to feed them.”

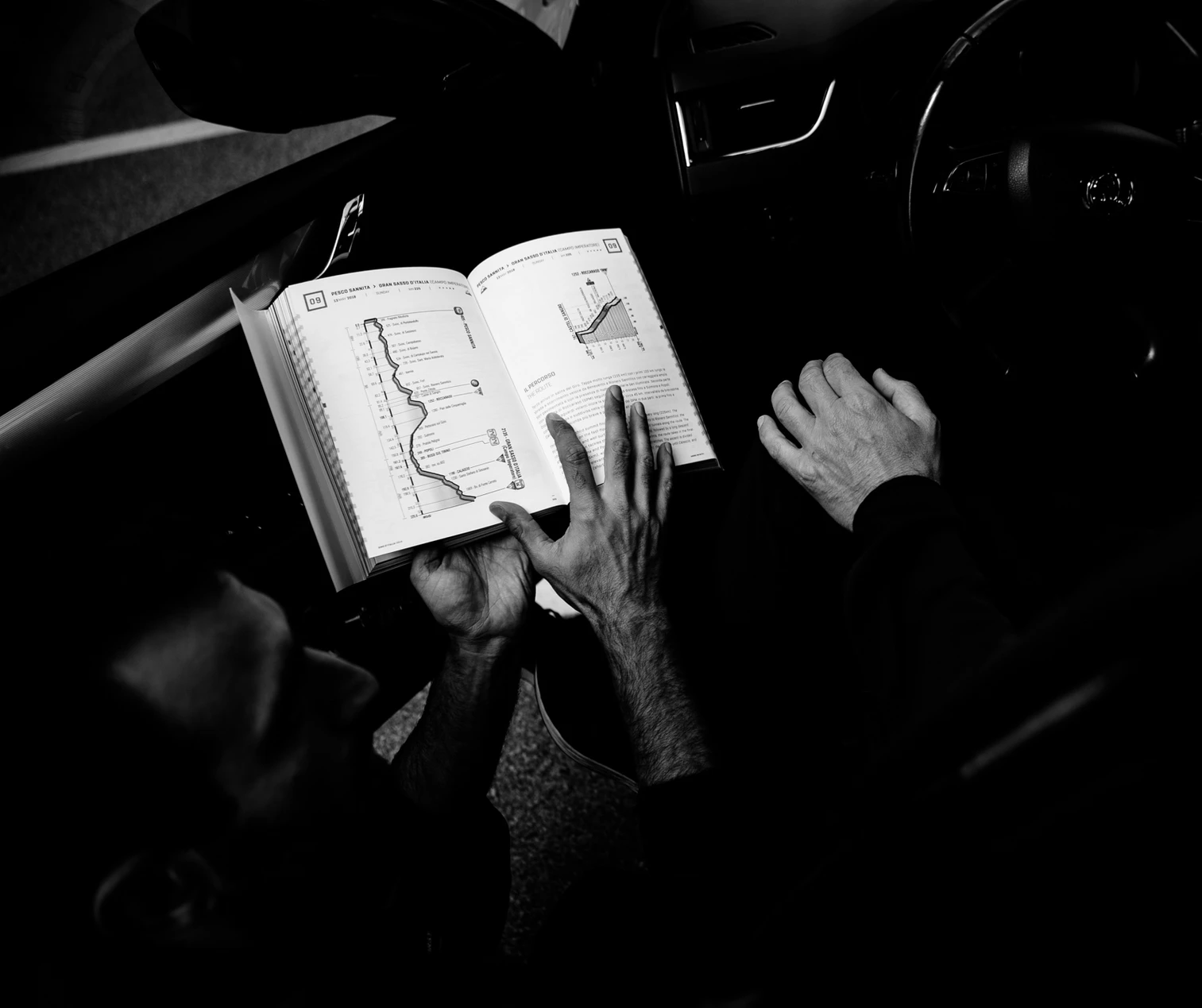

We jump back in the car and speed off after the racers. On this occasion we have to pass the group. This doesn’t normally happen, but on this occasion it must be done: roads are crazy in Israel, and the Giro has created quite a traffic jam! We’re in the race convoy for around 40 km, passing fans, kids and dogs and dodging roundabouts. This is sketchy, and you need to have your wits about you. The road is hard to pass at times, and Stefano’s stress level increases. When we have to pass through the peloton, it’s chaos, as riders hit our screen and don’t move over. The communication about support cars passing comes from race radio and then the DS (directeur sportif) should pass it onto riders. Luca says, “Some of them are mad as they don’t pass on this info. Instead they give the bidons to the riders whilst we’re trying to pass.” It’s a four-lane motorway with six cars wide in no organized manner and 170 pro riders. Stefano says, “It’s not easy, huh? Very stressful!” as we finally get through the peloton.

We speed down more closed roads and motorways to the finish, park up, and then the swannies sit down for a brief sandwich. This is the first time I’ve seen them eat all day, yet they are already discussing the post-race meal plan for the team. Will they eat straight away or at the hotel? We walk down to the finish amid cheering crowds. At the finish line, it’s like a reunion with all the swannies; gathering around a TV to see the final, most of the Italians are chatting with each other.

Sacha Modolo hangs his head, and Luca is right there with a bidon and a pat on the back. Stefano rushes around in a panic attending to the other riders, ensuring everyone is well looked after and—more importantly—that they know where the team car and van are. Back in the car park, riders are spent and reach for the food straight away. The job doesn’t stop, as Stefano re-packs the car and rushes around doing the other tasks so the team can leave.

This massofisioterapista (the Italian equivalent of soigneur) pair sum it up by saying, “The logistics, transfer from Israel back to Italy and having to cover many jobs is hard. You can’t always please the riders as there’s limited time. It’s all part of bike racing. After a three-week grand tour is done you’re happy to see the end of it. But after a few days you yearn to be back in the mix. The job is not for everyone and you must have passion, because without [it] you won’t last.”

On stage three I bump into Tom Scully, who’s heard about my ride with the swannies yesterday. Tom says, “Those two have rubbed a few Kiwi legs over their time. They’re two old hands and super good guys.”

Bidons provided: 400 new during Israel. 2500 new during the Giro d’Italia.

Post-race: One litre of protein shake, bottle of electrolyte and meal within one hour.