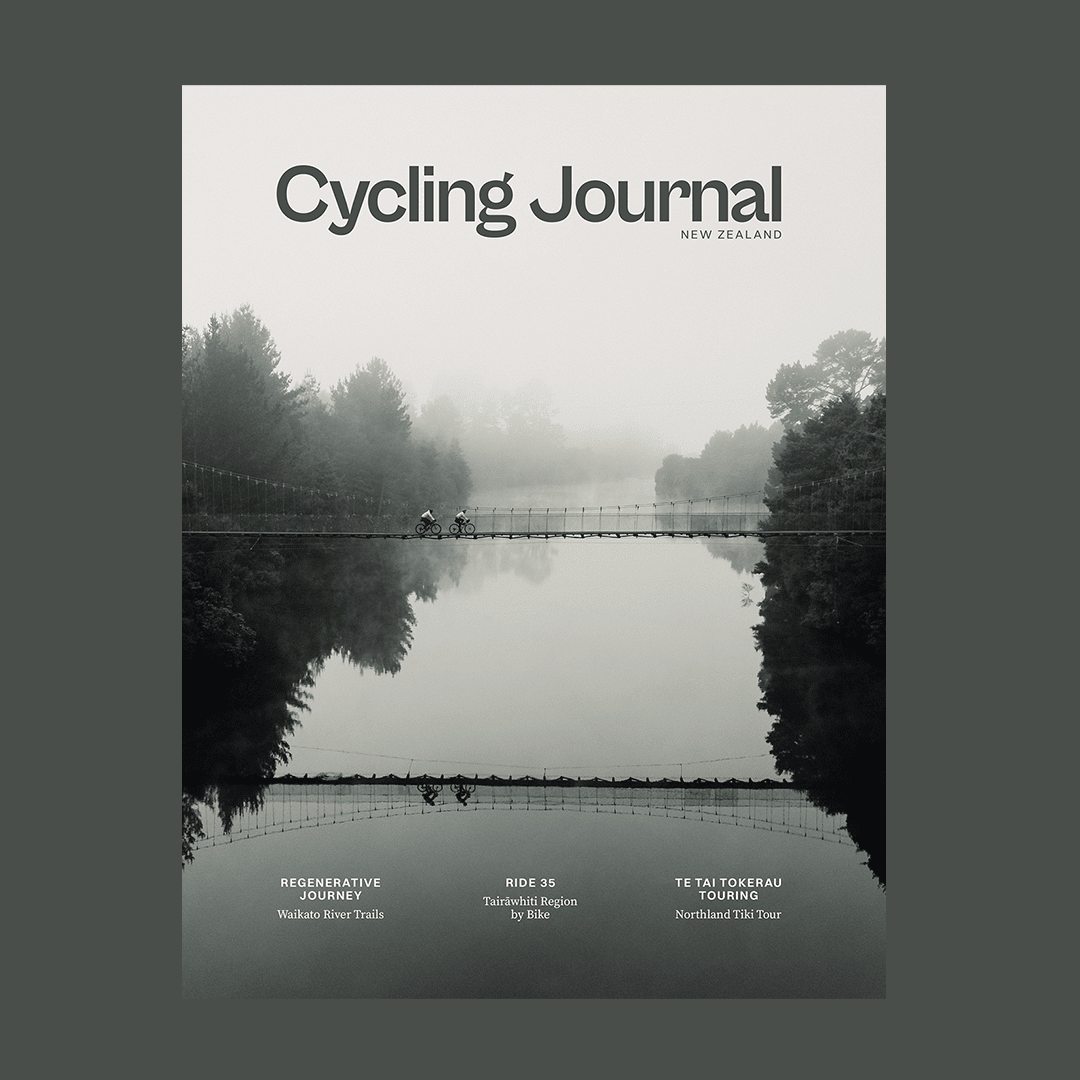

Words Liam Friary

Images Jakob Lester

A weekend escape is plenty of time to disengage from civilisation. Being immersed in the great outdoors for just 48 hours will make you question why most of us reside in concrete jungles. The constant ‘can’t make it happen’ reasons will always be there, but sometimes you need to break that thought pattern and actually make it bloody happen.

I was yearning to load up my bike and head into the backcountry, but was trying to figure out how to line up the logistics, weather – and people’s calendars. After several attempts, with dates being moved about due to a variety of reasons, we finally had it pinned and committed. I sorted the route and other logistics, and was getting excited. I wanted the route to have all the elements of road, gravel and singletrack, with an overnight camp. I hunted through DOC maps and already knew of several areas I wanted to explore; I compared heat maps and topographical maps to align a great route. I had two routes dialled, but one was more of a three- day mission and the other was an overnighter, so I opted for the latter due to time constraints.

Jakob Lester would be my ride companion and photographer for the trip. Jakob hails from Taranaki and is always keen to get into the local backcountry. He’s a good fella with a low-key vibe, is super dependable and a pleasure to hang with. The thing is, when you’re spending 48 hours with someone riding, camping and getting uncomfortable, you want to make sure they’re a good sort. Jakob’s quiet confidence and ability to be reliable in challenging situations made him the perfect companion for what would turn out to be more adventure than we’d bargained for.

The idea was simple: load up our bikes, turn the pedals, pitch a tent and return restored. But, during a quick scout of the maps a week before departure, I noted a large slip that hadn’t been cleared on the track we’d encounter. Turns out that was the least of my worries… but more on that later. I would rather a good trip, so got to making another new route. It still had all the elements of road, gravel and singletrack within Taranaki.

Day One: Into the Unknown

The morning arrived with perfect conditions—clear skies and a gentle breeze that promised to keep us cool without fighting headwinds. I’d spent the previous evening meticulously checking our gear and loading our bikes, ensuring everything was secure and accessible. The excitement of departure was palpable as I made final adjustments to our rigs.

Leaving the car behind in Matau, we set off through some historic tunnels before reaching our coffee stop with the Aeropress in Makahu Valley. It seemed appropriate to get some energy into us before hitting the first gravel section, which would eventually lead us to more of a broken off-road track into our camp spot for the evening. The coffee ritual was something we both appreciated—a last moment of civilisation before plunging into remoteness.

The road left farmland and entered dense regenerated native bush as we climbed over the saddle and swiftly descended into Aotuhia Valley. There’s a real sparseness out here—the feeling is that you are very far away from civilization. The summer heat kept beaming down on us and we applied more sunblock to our dirtied skin. Whangamōmona Road was rugged and a real blast on our fully loaded rigs. The papa rock formations can be a nightmare in the wet but luckily the summer had been mostly dry. A crew of 4WDs came through and we waved—we weren’t the only ones out there, though encounters were rare.

The rhythm of our pedalling matched the undulating terrain. We stopped occasionally to take in the vast expanses around us: densely bushed valleys carved into the landscape, the occasional bird call, a dramatic drop down to the river and the crunch of our tyres on loose gravel. The end of the road came into the small settlement of Whangamōmona, and we pulled up at the hotel for a pint and a bowl of fries. I chatted with the owner about our route for the next day, mainly the Moki Track. He laughed and said a few riders had come in a few years back saying the track was barely passable. Jakob and I didn’t really want to hear that, so we shrugged it off. Besides, that was a while ago. The cold beer washed down the dust from the road and, for a moment, sitting in the sun outside the historic hotel, everything felt perfect.

A discussion was had about whether we should ride a bit more to another camp spot, but after the food had settled in our stomachs and the blood had released from our legs, there wasn’t much energy for more riding. We set up camp beside the Whangamōmona river, in the campground, and watched the late afternoon sun cast long shadows across the valley. The simple act of pitching tents and organising our small camp brought great satisfaction. It’s these moments, when you’re ‘out here’ creating a temporary home that was carried in by bike, that makes self-sufficient riding so appealing for me.

Camping out with the stars at night is one thing— waking up to a possum trying to get into my frame bag was another! It wasn’t even scared off when I tried to shoo it away. After that, I wisely emptied the contents of my frame bag into my tent, knowing the possum would likely be back for round two. I drifted back to sleep and woke up to low cloud shrouding the steep, rugged hills. We packed up and headed out as the sun peaked out from behind the clouds and the day started to heat up.

Day Two: The Reckoning

The morning air felt different—thicker, somehow, with an electricity that hinted at the challenge ahead. We knew day two would be tougher, but there’s knowing and then there’s experiencing.

The main act for today would be Moki Track. What was described as a challenging route turned out to be a four-hour ordeal, bush bashing through dense vegetation with fully loaded bikes. The trail hadn’t seen maintenance in what seemed like years, with fallen trees and overgrown sections repeatedly forcing us under and over trees, searching for markers that were often hidden or missing entirely. Our pace slowed to a crawl as we alternated between carrying and pushing our bikes over obstacles that seemed designed to test our determination.

By midday, we found a small clearing with enough flat ground to rest and refuel. There wasn’t much talk between us as words alone couldn’t convey the beautiful brutality of backcountry bikepacking—or rather, hike-a-biking. After lunch, we continued along a particularly exposed section of trail, the ground falling away steeply to our right as we inched forward. The lack of maintenance became increasingly concerning—washouts had created gaps in the trail that required careful navigation, and we were forced to balance, lift and drag our loaded bikes across these precarious sections.

“This isn’t what I had in mind,” I admitted to Jakob, who nodded grimly as he hoisted his bike over yet another fallen tree. We both agreed there wasn’t much we could do about it now, and besides, we’d had an earlier discussion about how being this deep into it meant we needed to push through to the other side. The decision was constantly being debated in my head, rather reluctantly. We’d completed only half of the planned route through Moki Track, and it was starting to really take its toll. I kept reminding myself that I wanted to do this; we weren’t there by chance, we’d both wanted to explore this route and this is just what comes with the territory.

The ferns that immersed the overgrown singletrack route eventually opened up. I spotted cleared farmland on the hills on the other side of the Waitara River. We both tried to hold the excitement at bay…. could we finally be getting out?! The track plummeted us down a ravine and over a stile, onto farm tracks. There was a massive relief to be moving beyond walking speed and it felt good just to sit on the bike – rather than drag it over fallen trees.

The afternoon was getting on as we connected onto gravel roads. The navigation became increasingly complex as we searched for paper roads—legally accessible routes that existed more on maps than in reality. We crossed forestry land and negotiated with farmers for permission to traverse their properties. At one point, I got thoroughly muddled with the route and it was Jakob who came to my rescue, his calm demeanour a counterpoint to my growing frustration.

As the early evening wore on, our water supplies dwindled to nothing. The summer heat, rolling hills and hard gravelled roads had me waning. We were beyond buckled—that special kind of exhaustion that comes when you’re mentally and physically depleted but still have miles to cover before safety. The final section to the car seemed to stretch on infinitely. Despite our exhaustion, we summoned a final burst of energy, pushing hard along the last stretch of gravel road. Our determination had become something primal—the pure instinct to complete what we’d started, regardless of the cost.

As we approached a small cluster of houses at our endpoint, a man emerged from his home, curious about the two of us outside his property. “Where’ve you fellas been?” he called out, and we stopped, gratefully accepting his invitation for cold water. As we gulped down the refreshing liquid, he mentioned that he and his neighbour had been keeping an eye on our car, wondering if they might need to call search and rescue if we didn’t return soon. The simple act of loading our bikes onto the wagon was monumental. We shed our sweat-soaked kit, the relief of changing into clean clothes almost indescribable after two days in the elements.

Jakob summed up the ride perfectly: “We know that life isn’t easy, but when it’s hard we want it to be easy.” That’s the beautiful contradiction of adventure—we seek out difficulty voluntarily, push ourselves to – and sometimes beyond – our limits, all for those transcendent moments when everything aligns. When the struggle gives way to flow; when discomfort yields to discovery. Our weekend escape had been more challenging than anticipated but, as we drove home under a darkening sky, I knew we were returning to civilisation changed in subtle but meaningful ways.

Sometimes the greatest adventures are the ones that don’t go according to plan. The ones that strip away pretence and comfort, leaving only determination and companionship to see you through. In those moments of pure struggle, something essential is revealed—about the landscape, about friendship and, most importantly, about ourselves.