Words by Liam Friary

Images by Cameron McKenzie

Tiki Tour Noun. New Zealand. A scenic tour of an area.

The bike takes us to unique places, and can enrich any experience it’s a part of. It’s a portal between us and the environment; offering insights and perspectives of the land and its dynamics. It’s quite something to reside on Aotearoa, New Zealand, a small Motu (island) in the South Pacific – there are rich in landscape, history and storytelling.

One of these locations is Te Tai Tokerau (the indigenous Māori word for the Northland region), which offers a raw, rugged beauty unlike anywhere else in Aotearoa. The Whenua (land) is enthralled with a rich and turbulent history. I’m not going to document all of it here, as that’s for you to do your own research. However, with knowledge and respect, we can continue to learn from one another. I was eager to explore this remote land at a slower pace, by bike. What I didn’t expect was how this journey would flip my perspective and immerse me in another world.

A ride experience like this is better shared, so I reached out to the riding community to find a rider who has Whakapapa connections to this Whenua.

After some dialogue, coffees, lunches, rides and getting to know one another, I knew Matua Murupaenga was the right homie to have riding alongside me. I flicked him over the rough itinerary and his immediate response was: “I’m in bro”. Matua would not only be my riding companion, but offered guidance with Māori customs, protocols and knowledge along the way. He was most excited about riding across the whenua (land) where his Tīpuna (ancestors) are.

Matua’s comments ahead of the trip: “Riding bikes is the purest mode of transportation and exploration. It’s something difficult to explain, but cycling in all its forms opens endless possibilities for our body to connect with the land. For me, it was obvious from the moment I was approached to be a part of this kaupapa that it would be something special. Being in Te Tai Tokerau is one of the places I really feel happy, but it’s not often I get to go there to ride bikes. Going back to childhood memories, images of my teenage years getting the bus up to Hōreke for school holidays, visiting my mum who was living there at the time. This trip was an opportunity to revisit places in the Hokianga on my own terms.”

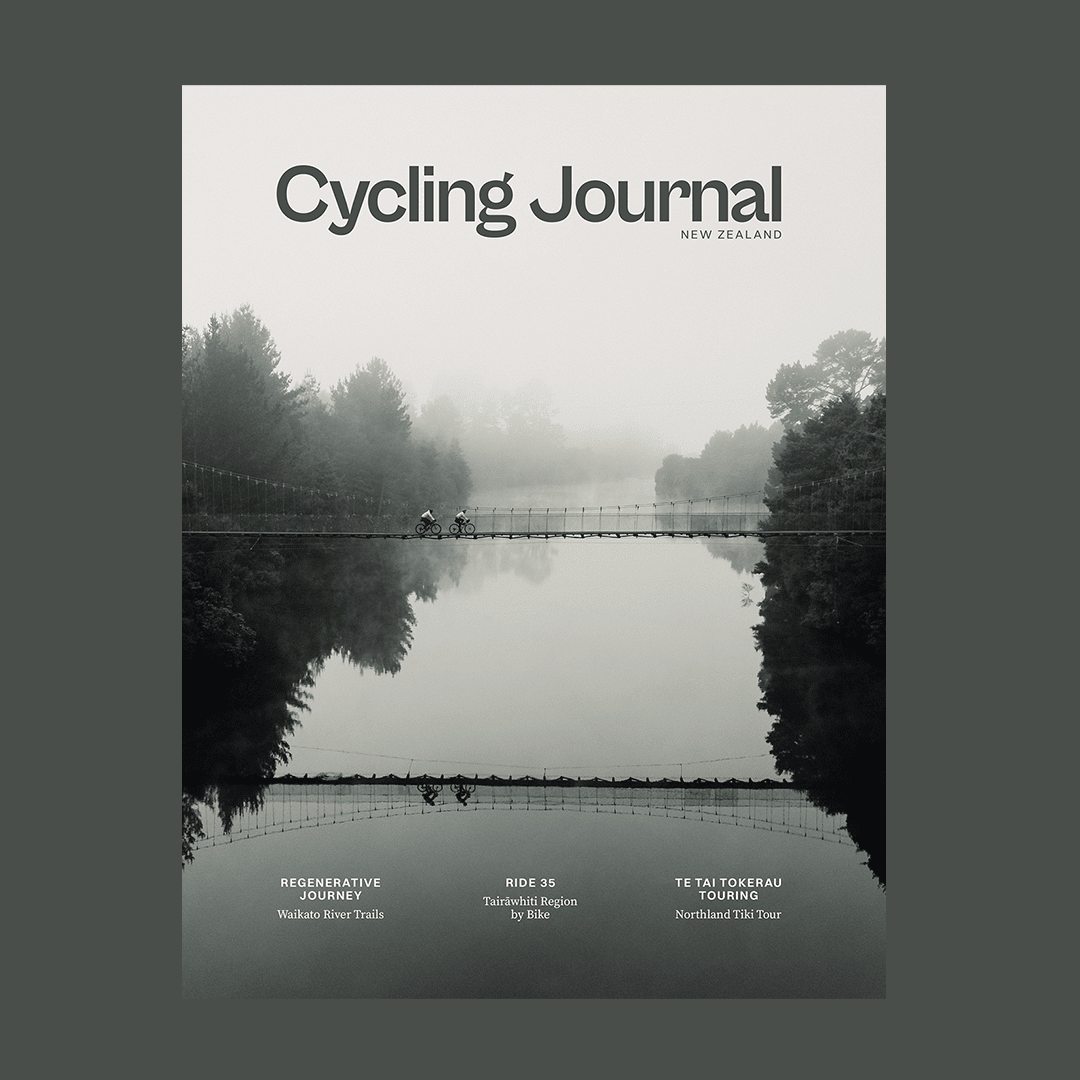

The road trip north was filled with kōrero (chat) and Māori musicians that Matua introduced me to. The rat race was left behind as we transitioned to a slower pace. Te Tai Tokerau is only a few hours from the biggest city in Aotearoa, Tamaki Makaurau (Auckland), but feels like another world. So, with that in mind, it wouldn’t be a hard and fast ride from A to B, but rather a ‘tiki tour’ across the whenua. This would allow us to be present during the ride, see landmarks along the way, meet unique characters and allow the stories to unfold organically.

The trail: Pou Herenga Tai / Twin Coast Cycle Trail would be our arterial route, connecting both the east and west coasts of the upper North Island, cutting through bush and farmland. This is one of the only Ngā Haerenga Great Rides of New Zealand to touch both coastlines of Aotearoa, making it especially unique. Te Tai Tokerau narrows as it reaches further north, so it’s great you can explore both coasts without a massive haul between them. For this trip, we’d head west toward the Hokianga Harbour, then east to the Bay of Islands— experiencing both diverse coasts between the narrow land mass. Our route would mix purpose- built bike trails with back-country gravel roads, allowing us to experience riding mainly car-free.

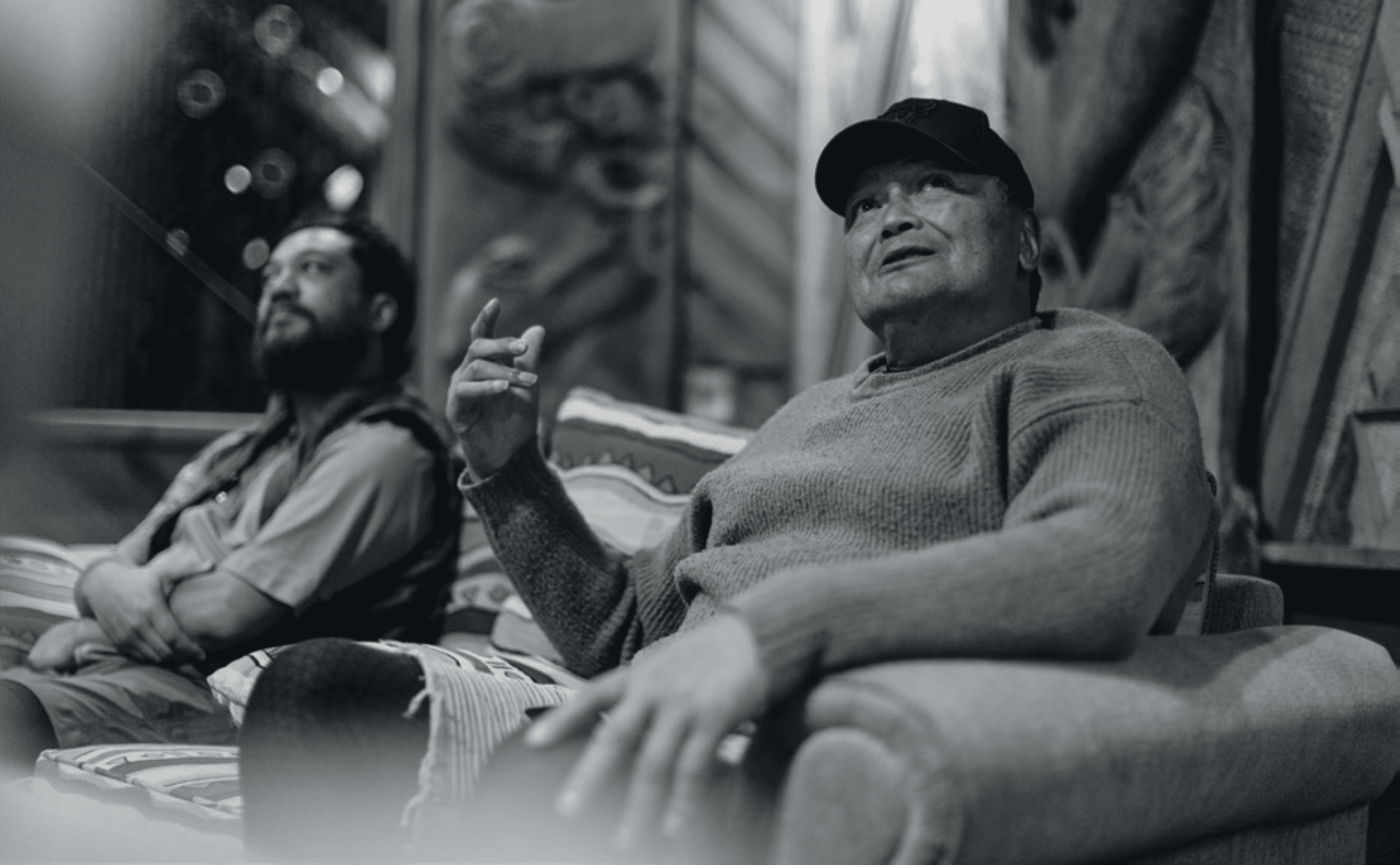

Our journey began with a welcome onto Kohewhata marae (Māori meeting ground) just outside of Kaikohe. First came the karanga (a welcome call to all visitors walking onto a marae), then we walked slowly towards the wharenui (Māori meeting house). Out front, we removed our shoes and entered this sacred space; I immediately felt the strong presence of wairua (spirit). Large carvings of tīpuna can be seen on every pou (pillar), as well as the side and the ceiling of the wharenui. We were welcomed and acknowledged with Manaakitanga (hospitality and respect).

Matua’s comments: “I remember patiently waiting to be called into the wharenui. Seeing the kaikaranga in the shade of the entrance, visualising the speech I would need to deliver on behalf of our crew during the pōwhiri; the best koha we could give back to this kaupapa is to tell an authentic story of this adventure and the places we visited along the way.”

Afterwards, we shared some kai (food) in the wharekai (eating house) which is tradition for Māori. The overnight marae stay was a truly unique experience, sleeping among the tīpuna of Kohewhata marae. Just before dawn, the kaumātua (Māori elder) returned for a karakia (prayer), blessing the day and the journey ahead through Te Tai Tokerau. After a brew in the wharekai, we packed our bikes and headed toward the west coast.

We rolled onto the Pou Herenga Tai and skirted around Kaikohe, past Lake Ōmāpere with its morning mist being warmed by the sun rising from the east coast behind us. The first place for kai was the Kiwi Kai café in Ōkaihau. A few locals rolled up for their morning pie and coffee; it was evident most folks around here know each other. Almost everyone greeted us with “Kia ora” and a smile. The fresh handmade pies were delicious and gave us sustenance for the next few hours, as there wasn’t much between here and the Hokianga.

The trail led us through tighter lanes descending alongside an awa (river) where vast countryside gradually transformed into tighter singletrack bush before opening again into faster, straighter gravel sectors. Tino Rangatiratanga flags (Māori sovereignty flags) flew outside many houses and marae, scattered across the landscape. Nothing here resembled suburban development— space between neighbours was abundant, a stark contrast to urban sprawl found in the major cities.

After a fight with the prevailing westerly headwinds, we approached the edges of the Hokianga Harbour. We crossed a long boardwalk—the longest in Aotearoa, at just over a kilometre—over mangroves before reaching Hōreke; small, quaint and laid back. Randomly, we bumped into an uncle of Matua’s, riding his quad bike—he handed us some fresh fruit stashed inside his cardboard beer box. Yum— it was so fresh! Our overnight stay was at beautiful Riverside Villa accommodation which didn’t disappoint—not to mention, the homemade kai was great too! After that, we headed to the neighbour’s, ‘Franks’, a local spot in what was essentially a corrugated iron shed serving as a gathering place. It had it all—beers on an honesty tab (cash only), pool tables, darts and plenty of relics from years gone by. Frank’s stories of the area offered insights that could only be learnt by being there in person. His personality was infectious, asking us all about our individual stories. Frank’s manaakitanga made the iron shed feel warm.

It was only a few days in, but the people we’d met so far were so genuine. Always asking ‘what yous up to?’ and ‘where yous heading?’. Matua’s connection to this whenua was present as every kōrero—especially on the west coast—resulted in him either knowing or being related to that person. A hug, a few jokes and lots of smiles were shared with one another. As with many of these stops on our journey, we’d bump into the same folk two or three times as some of these places are small. Each time they’d kōrero, growing a relationship with us. We felt welcome everywhere we went, and were always wished safe travels on departure.

The Hokianga is so vast. I took time in the ata (morning) to move slowly and sip a brew as the sun rose over the harbour, flanked by the Maungataniwha Range in the distance. The sailing across the Hokianga, on the Ranui, let us appreciate its significance for Māori in the early years. This is where the great navigator Kupe first arrived. Kupe was a very early exploring ancestor—most say the first of the Polynesian ancestors to arrive here in Aotearoa from Hawaiki. It’s also home to Māngungu Mission House which is where the third (and largest) signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi took place. We departed the ferry in Kohukohu for a short but undulating lap, mainly on gravel, eventually returning to catch the car ferry to Rawene.

There was certain haste about Matua and I scrambled to stay on his wheel, hustling back to Kaikohe on Pou Herenga Tai. I understood why—we needed to get some kai and have a soak, all before the day was out. I took another sip from my bottle, scrambled for snacks in my frame bag and got on with proceedings. The Kaikohe Bakehouse is an institution, and we frequented it many times when riding back and forth. We pulled up from the ride and ordered a large munch—and boy, did it deliver. A soak in the geothermal hot pools of Ngawha Springs rounded out the day perfectly, and we ended the evening with tired bodies and full puku (stomachs).

The fast-paced hustle of city life had well and truly disappeared after the third day of being immersed in Te Tai Tokerau. There’s a certain sense of space and time up there. The journey out to the busier Bay of Islands was mostly flat gradients, with fast-rolling sections through open farmland alternating with tighter, dense bush sectors. This swift ride took us through Ngapipito Valley and over Twin Truss Bridges at Tūhipa. The Pou Herenga Tai brought us to the outskirts of Kawakawa, then onto a historic train ride to Opua. Perhaps we were a little too laid back for the train conductor’s liking, though, as we were a touch late and got a hurry up phone call. The short ride off the train was to the car ferry across to Russell. This hilly land, along with the stop-start transfers, truly emptied the legs as we nudged closer to the seaside settlement.

There’s so much contrast to each coast—rough raw energy on the west coast, beautiful pristine shores on the east coast—displayed by the land, housing and population on each. Some of these places have been left to ruin through years of neglect by consecutive governments and ongoing land confiscation disputes. For me, it’s hard to hear these truths but rather than being paralyzed by it or ignoring it I am motivated to do my bit and learn more about the history of Aotearoa, New Zealand.

There is ever-changing scenery whilst traversing the narrow land between coasts. This encapsulates Northland’s diversity perfectly: from mountains, bush and inland farms to picturesque waterways and coastline—all in a single day’s ride. After the historic train ride, and a water crossing, we descended into Russell (New Zealand’s first ever capital) during the twilight hours. In need of kai, we rolled straight into Hone’s Garden. Fresh oysters, craft beers and wood-fired pizzas offered the most upscale experience of our trip. While enjoyable, I found myself missing the authenticity of the deeper parts of Northland we’d experienced earlier.

As we packed up our bikes, I reflected on what makes bikepacking through Northland unique. It’s the people and manaakitanga; the hospitality, kindness, generosity, support—the process of showing respect, generosity and care for others. Unlike traveling by car, the bicycle slows down the speed and puts you at ground level with the land and its people. You feel every pedal stroke, hill, gust of wind and change in the landscape. Perhaps most importantly, you’re approachable. That approachability opened doors to conversations and connections that might have otherwise passed us by.

The whenua we traversed, the wairua we encountered, and the stories we collected are now permanently etched in my memory. This journey by bike isn’t just about the physicality of travel—it’s about moving through living history, experiencing a cultural immersion, and finding common ground through shared adventures and mutual respect.