Words & Images by Tom Powell

Packing camera gear for a trip like this becomes a task all its own. For months, as the idea of riding Peru’s Great Divide took hold, the questions kept circling: which lens to take, how many batteries, whether the weight of a drone was worth it. How many memory cards? How to back everything up if things went sideways? At the end of that long, meticulous list, almost as an afterthought, I threw in a couple of old film cameras – just for the fun moments. Just for myself.

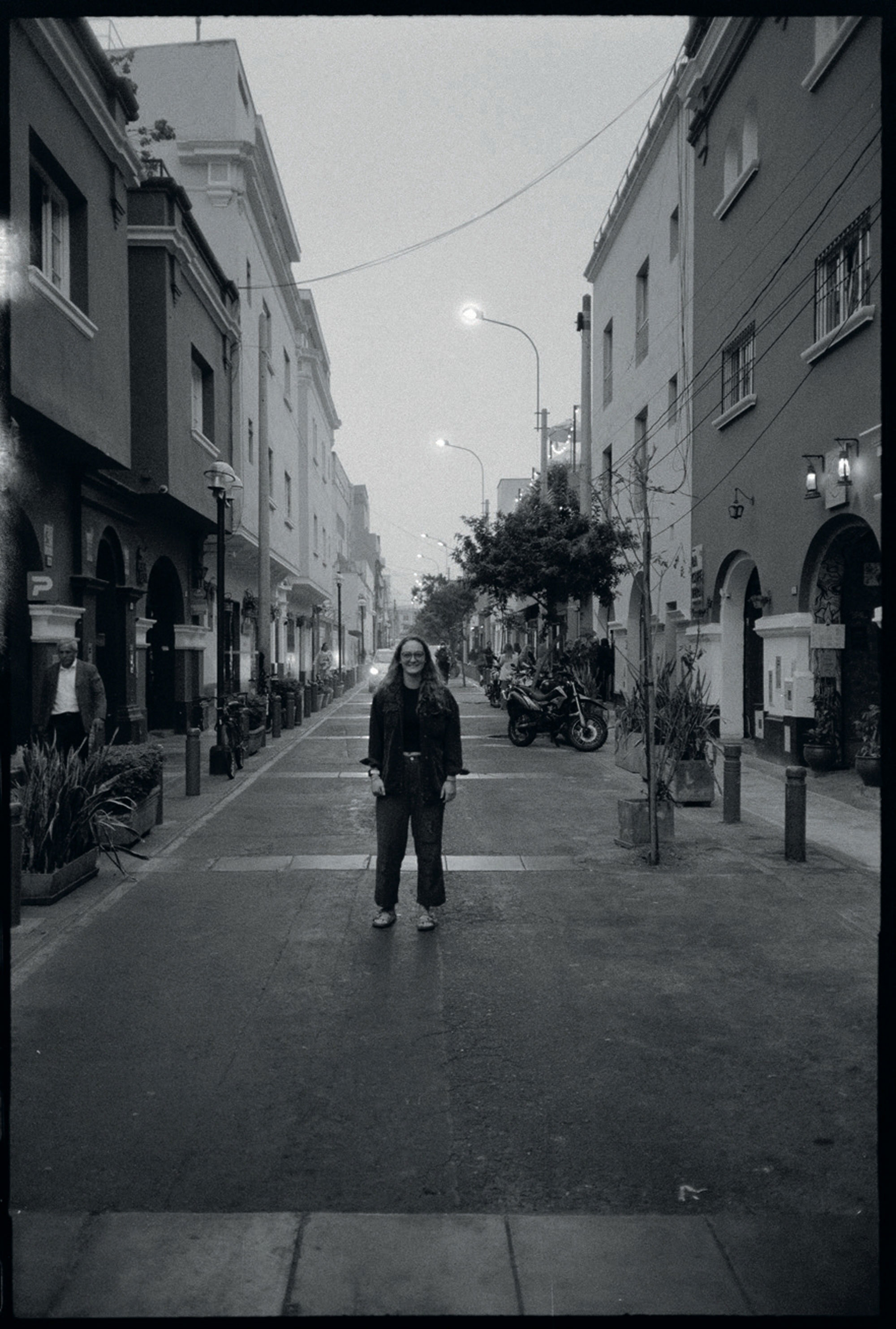

When we set off along Peru’s Great Divide, I figured I’d document it fully: two cameras, a bag of batteries, and about 5000 digital frames by the time we were done. The plan was simple – the digital shots would tell the story. The film cameras were just behind-the-scenes moments, something extra to sit quietly in the background.

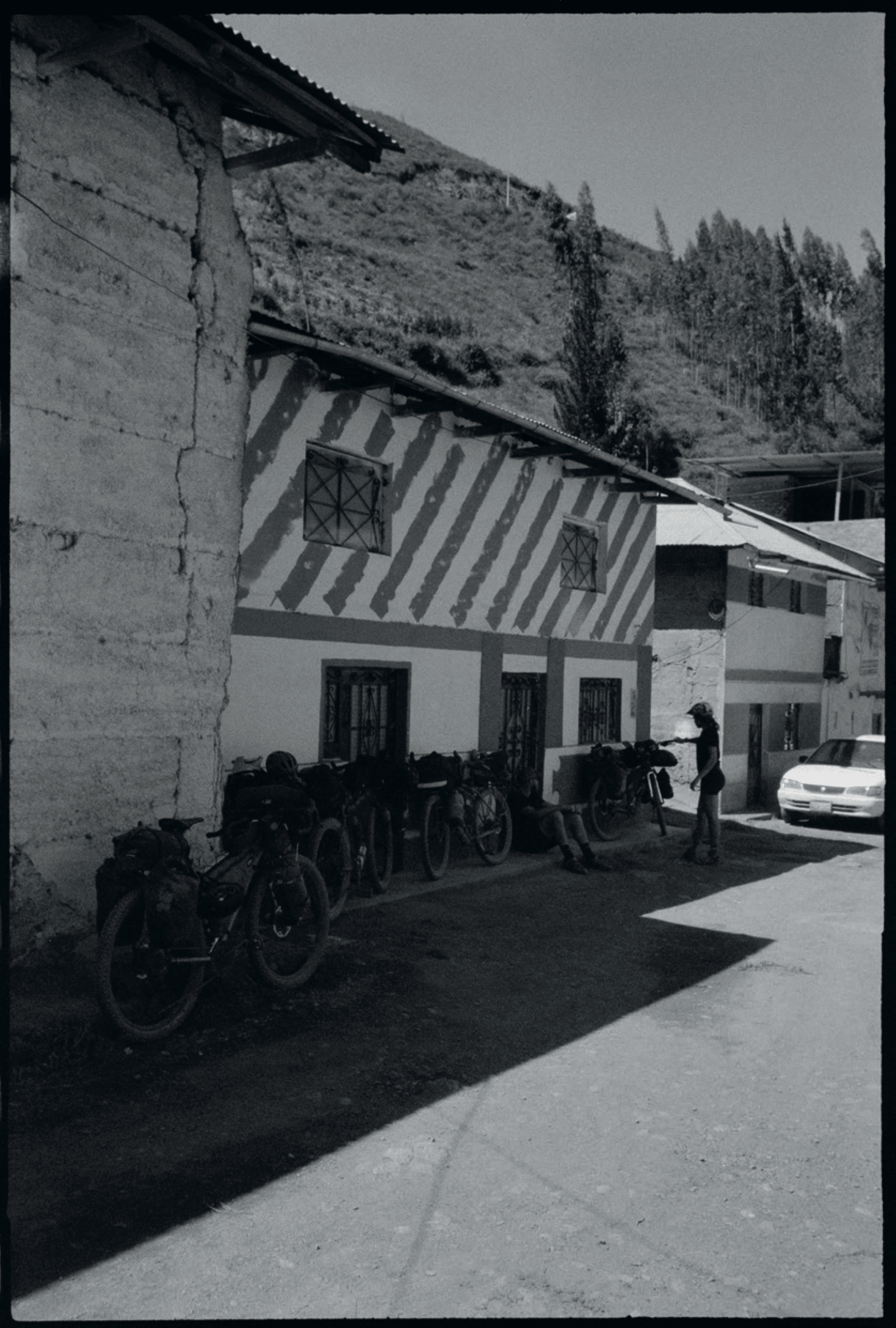

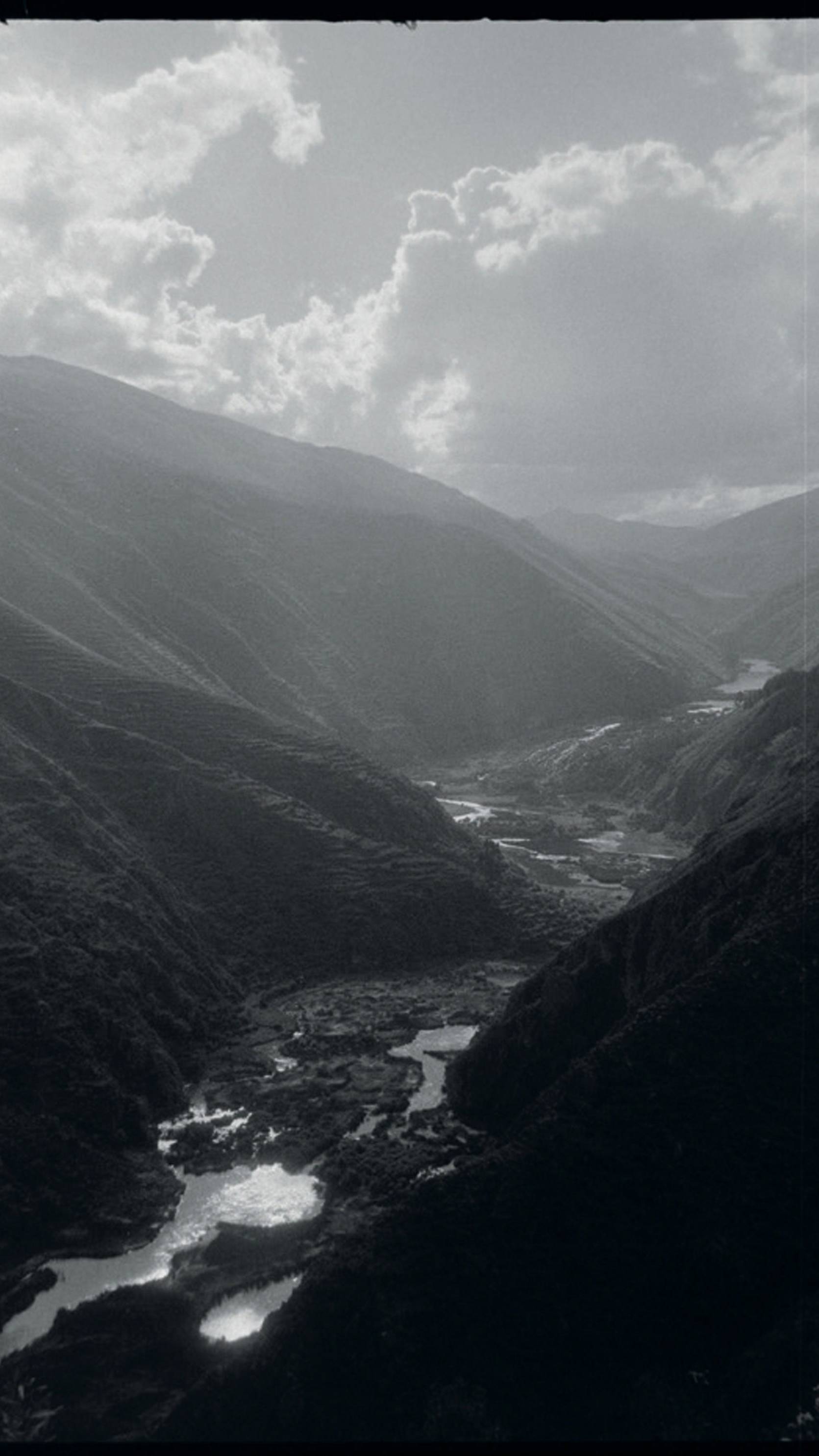

At first, it worked exactly like that. The digital photos captured the landscape the way I thought it needed to be seen – clean, sharp, vast – every mining road, river crossing, and ridgeline laid out in perfect detail. I was shooting every moment, crafting the epic bikepacking story I’d built in my head, ticking off scenes like a shot list. Sometimes even re-riding secti or lining up compositions – a quiet nod to the marketing managers who might, someday, care. The film cameras just rattled along for the ride, stuffed into dusty frame bags and pulled out whenever I could be bothered.

The riding itself didn’t leave much energy for overthinking. The divide dealt us a steady diet long, slow climbs that lasted entire days – layered with a constant background hum of fatigue, food scarcity, and the constant altitude sickness that made any task more difficult. Mornings were cold and dry, afternoons were endless slog, and every decision started to feel heavier than it should have. Even the thought of digging out the digital camera from my hip pack sometimes seemed like too much effort.

More often, I found myself reaching into my feed bag, brushing past a crumpled packet of Oreos to pull out one of my old film cameras – an Olympus Mju II or an Olympus Trip 35. Small, simple, mechanical things. Not precious. Not fragile. Not demanding anything more from me than a half-second to frame and fire.

At the time, it all still felt like it was going to plan. I was building the digital story I’d imagined – the big, clean narrative of remote landscapes. Thin air, dusty switchbacks, and hard-won progress. It wasn’t until I got home, months later, that the struggle began. Sitting with thousands of digital frames, trying to stitch them into something cohesive, the story I’d set out to tell began to slip away from me. The digital gallery mapped the ride I’d imagined. The film frames captured the ride I actually lived.

The tired faces. The empty stretches were nothing much happened except the slow passing of hours. The moments where the road dissolved into rubble and the trail ahead seemed too far to bother with. The way the mountains pressed down on us. Quiet and endless. The mess that didn’t fit neatly into a frame or a caption.

By the time I finished sorting, I had a hard drive packed with 42 megapixel images – and a few rolls of battered film that somehow felt more alive than all of them combined. Funny thing is, when I show people the photos, it’s always the film shots they stop at. The dust, the grain, the broken light – it’s thhose frames that catch people, that explain something about the ride that the polished shots never could.

Both sets of images are honest, in their own way. The digital shots tell the story I set out to tell – clean, complete, curated. But the film – the side project, the afterthought – tells the story that actually happened. The messier version. The smaller, colder, dustier truth. The story I didn’t even know I was telling at the time.

Even now, months later, I still find myself sifting through the digital shots, trying to pull some kind of narrative from them. Thousands of images, all technically perfect, all waiting for a story I’m not sure how to tell. Nine months on, the gallery feels as wide and endless as the mountains we crossed – detailed, beautiful, but overwhelming. Meanwhile , the film shots just sit there, already edited by their own limitations, each frame a decision made in a split second. A version of the story thatt needed no stitching together, no second guessing. Maybe one day I’ll find a way to share the digital set. But for now, it’s the dusty, battered frames that tell the story best.

Adventure rarely plays out cleanly. Memory even less so. Sometimes the best record you can hope for is the one you didn’t mean to make – battered, blurred, beautiful in a way you only understand once it’s already over.