Words & Illustration Robyn Glendinning

It’s a mild day on a winding, potholed, single track road on the banks of Loch Awe (on the West Coast of Scotland). Pines and oaks hang overhead and a rusted sign points to an old, rutted cattle driving path over the hills.

But today, there are no adventures in the forestry, nor kilometres traversed by pedal power. No, today a small child with a short blonde bob is screaming at her dad, adamant that he must not let go of the back of her saddle under any circumstances. Her stabilizers have been forcibly removed, according to her. No one is having a good time, apart from a younger sibling merrily pedalling back and forth along a short stretch of the quiet backroad. The screaming child is me. I would like to say I’ve grown out of losing it in the face of scary things. But that would be a lie. I regularly worry about my boyfriend’s hearing on caving trips. And my old work colleagues from conservation were used to hearing my yelps of fear amongst the head high gorse and forestry slash. But I’ve always done the things that scare me despite the bucket loads of fear and anxiety that love to come along for the ride. Because, at the end of the day, I don’t want to live with the regret of not doing them.

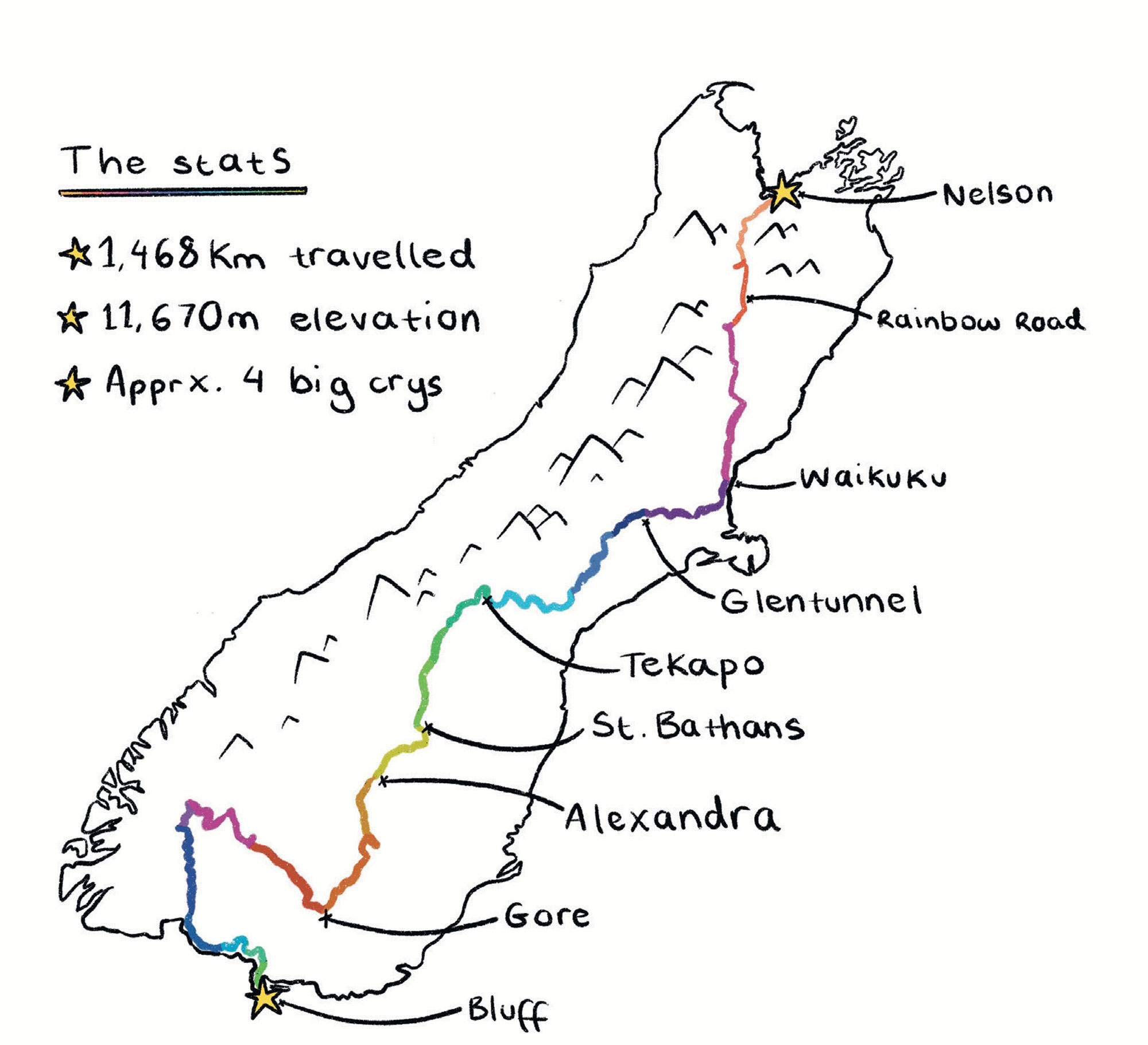

Which is how I found myself cycling from my home in Nelson to Bluff, alone, on a nearly 1,500 km journey. Not racing, not rushing, just following a convoluted collection of trails and gravel roads from north to south. Because despite my rural upbringing, overnight tramps and multi-day bike trips were never on the cards, so I didn’t camp by myself until I was in my late 20s – and I was scared stiff for most of that night (crispy heather rustling on a tent fly sounds really creepy, okay). Through much trial and error I’ve come to a place of peace with bikepacking solo. I know what I like (climbs and cafes) and what is challenging (steep downhills and solo camping). I am quite content with my own company, and this has come from practice and necessity. Solo riding has its challenges for any rider; for example, you can’t share the weight of gear, and conversation can be a bit thin on the ground (thank goodness for audiobooks and podcasts) but it’s ultimately very freeing. Eat when you want, sleep when you want and do however many kilometres per day as you feel like.

There are no rules. Apart from the highway code, which I adhere to strictly. Distance travelled in a day doesn’t equal worth. Deviating from the guidebook route is just fine. Once I let go of the need to do big days every day, for days on end, I felt calmer and enjoyed myself more. I chose to take a short day when I knew it was going to rain overnight in Twizel. But I also chose to go up the Omarama saddle in the rain, with poor visibility because I knew I could handle it, and it outweighed the risk of getting stuck in a small town with more bad weather moving in. For the most part, I am a conservative rider when it comes to risk, but I chose to not carry a PLB on this trip (I had daily live tracking via my Komoot app) because injury and mechanicals aren’t the things that worry me. Other people worry me. Being harassed by a Ute load of drunk men for example. But it didn’t take going into the high country alone for that to happen; all it took was exiting the New World carpark after getting groceries with my boyfriend, at the wrong time on Boxing Day. And setting off a PLB wouldn’t have helped in that situation. Keeping calm and de-escalating would. Or just booking it far, far away as fast as possible.

I don’t like to dwell on this murkier side of solo travel as a woman for too long. Because just like with everything, risk exists. Downhill mountain biking is inherently dangerous. Climbing and bouldering, also sketchy. Cold water swimming, using a chainsaw, moving halfway around the world all by yourself and going caving every other weekend. All dangerous, all risky and all things I have done. But all done with safety precautions in place and practice. With learning to climb, I can physically see the safety I am adding to my harness. But with biking, I find myself riding down an invisible line of how much energy, money and time I want to expend on mitigating a risk I have no control over. So I chose no PLB on this trip, but I did have live tracking and a repair and first aid kit that I was comfortable using. I know my limits when it comes to weather and terrain. I’m polite and courteous to other road and trail users and, just in case, I do know karate. If a man approached me on trail, would I become more aware? Yes, of course. But I don’t let it dictate how I spend my time. I don’t make myself or my bike any less visible, in fact I am be-decked in high-vis and multi-coloured bags. I try to bring my most authentic self with me, because I’m here to enjoy myself. I’m here to experience all the joyful moments that bikepacking offers.

The joy was discovering that my bright blue dry bags and yellow high-vis were a major attraction for bumblebees. I was one giant flower to them, slowly pedalling across the landscape. Conservations with other riders were a source of humour and admiration. Meeting a French couple in Mossburn who, despite their heavy traditional touring set-ups, made the journey through the Rainbow Road on super skinny gravel tyres. Or the cheery Dutch man who, after I explained how I’d pushed up most of the Omarama saddle rather than riding, responded with a cheeky grin that; “Well, it is a push bike”. Throughout the trip I was met with kindness, and a few raised eyebrows. People can be kind but also think what you are doing is crazy – and that’s ok, I don’t think bungee jumping, or tandem skydiving sound very fun.

Travel by bike immerses you in the landscape; I got to see a flock of Silvereyes feasting on wild cherries as I paused on my ascent of Burkes Pass. I knew straight away I was getting closer to St. Arnaud when the smell of honeydew flooded my nostrils. All the headwinds and crappy overtakers were forgotten when I realised I was getting a private show of the last of the season’s lupins. Or that I have every reason to stop at cool cafes and weird attractions in small towns and sample the delights of the local Four Squares. And, even when I’d spent the morning having a cathartic cry whilst packing up my tent, I knew in a few hours I was going to see something wonderful. Fresh snow on the ranges, the Clutha/Mata-Au river in all her powerful sweeping glory, or a really good deal on steak and chips.

Solo endurance travel, for me, is an exercise in self- care and knowing my limits. I know I can do 100km plus days but that not every day has to be that. I know I could save money and buy the cheaper cereal bars, but the next day when they are the only thing I have for lunch I’d rather have the ones I really like and not the ones weirdly reminiscent of cardboard. There is no prize for doing it the hardest after all. I happily chose a hot tub and cabin over camping in the rain. And I’ve learnt that I really should pack my eye mask for sleeping because even though it feels like a silly luxury item it helps me sleep and it would have saved me cash on motel rooms when I was sleep deprived a week into my trip.

I’ve learnt that despite all the risks and challenges and fears, nothing feels quite like completing a journey that has been years in the making, of proving to myself that I am more capable than I previously believed. And despite my fears, the only things that caused me grief on this trip were a slightly sore knee, a touch of carpal tunnel and a plague of possums chittering outside my tent at 1am.

Robyn is an illustrator, designer and content creator based in Tasman. You can follow her adventures and creative work on Instagram @robyn_glendinning